Working at an antiquarian bookshop can at times be life-changing.

Before I turned to the profession of teaching, I worked for a brief time in an antiquarian bookshop in Kundapur. Back then, antiquarian bookshops were rarer to find than the rare books they specialised in, so I grabbed the opportunity to work in one even though friends and family thought I was wasting time. It was by chance that I even found myself there — an old school friend whose home town Kundapur was, happened to step one day into a stationery store and found to his amazement that they also sold rare books. The shop — which I’ll leave unnamed — had a signboard that read: Stationery and Antiquarian Mart! What’s more, the owner, Mr. R, was actually looking to hire a store assistant.

I rushed from Bengaluru to meet Mr. R, a gaunt man with a closely trimmed salt-and-pepper beard in a white cotton veshti and bright terylene shirt, who straightaway put me through a strange but oddly satisfying interview. “You take coffee?” he asked me first, and when I said yes, he set me a task before excusing himself to fetch the coffee. He had picked from his bookshelves three books of varying formats — a quarto, an octavo and a duodecimo — for me to describe in cataloguing terms. R looked approvingly as I rattled off “4to, 8vo and 12mo.” He urged me to have the coffee, which was pleasantly strong and aromatic. “One last thing,” he said, thrusting an unruled notebook and pencil towards me. “Draw a book, showing all its parts and name them.”

It felt like being in school again, in a biology class drawing and naming the parts of a flower. Amused, I set to it, relishing putting arrows against the parts — gutter, text block, hinge, backstrip, pastedown endpapers, recto-verso, half title page, etc. “Excellent, you’re hired.”

Actually, what I wanted more than a bookshop assistant was someone who can catalogue the stock correctly. Have you found a place, yet? No? Well, no need to look — you can board and lodge here. We have a room on the terrace you can use; you can take your meals with us. My wife is a fine cook; but no seafood and all here, okay, we are pure vegetarians.”

I soon discovered why they say that ‘the antiquarian booktrade is the last resort of the Indian eccentric.’ The price of each edition was marked lightly in pencil at the back of the book, but R, even when the customer was glad to pay the marked price, was reluctant to sell a book until the customer was willing to bargain over the price. Somehow he managed to insert a bargain into each transaction. “You have to give them a bargain, I say,” he would tell me after the customer left, “only then will they leave satisfied and come back again.” In any case, there was only the occasional customer; I was surprised anyone in town even knew the stationery store also doubled as a rare bookshop. If a customer buying pencils or notebooks bothered to peer in one dim, dark corner of the shop, she would see a tiny cardboard sign saying ‘Rare and Fine Books Inside’, with an arrow pointing to the back.

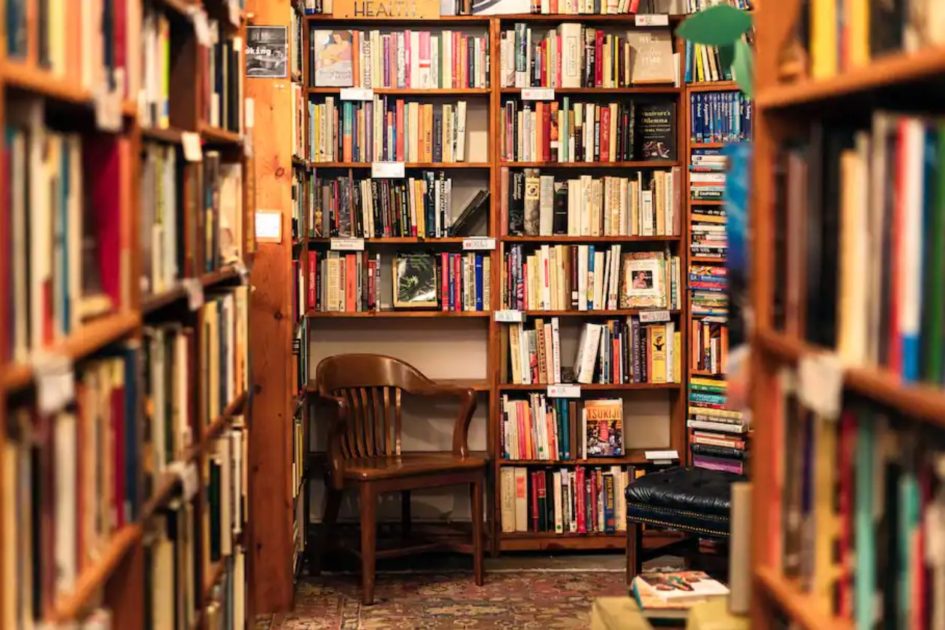

This was the larger room behind the stationery store-front, crammed from floor to ceiling with books. There was more: R never kept the best books for customers to see or browse through — all the high-end antiquarian editions were stowed away as his personal loot.

I discovered this was the case when I found a few of them mixed in with the rest on the shelves, and had begun cataloguing them. R registered this with alarm: “Why why why are you cataloguing these, I say! No no no no; only for own use, I say, own use only, okay?”

His wife, a gentle, kind, and long-suffering lady, looked like she had had enough when she discovered this — apparently this was not the first time that book purchases were secretly being split into stock and ‘own use’. It had been a long quarrel between them, that he strictly buy expensive editions only for stock and not for himself, but R, unable to resist adding to his own collection, had sneaked many recent expensive purchases and disguised them as stock.

If a customer picked one of these to buy, he would politely and cunningly find a way to discourage them. A short while after this — roughly six weeks after I had begun working at The Antiquarian Mart — the whole operation blew up, bringing my apprenticeship, as well as the rare book business, to a close.

Returning one day from one of his far-flung book buying trips, R was, as surreptitiously as possible, smuggling in his loot when his wife caught him red-handed. It was only later, after I had said my goodbyes to The Mart, that I realised how bored R must have been selling stationery over the years, and how turning that back room into a rare book business must have seemed such a longed-for escape. And how, slowly over time, those incomparable editions had worked their magic on him, completely possessing him.

As for me, I have always felt grateful for that short time spent in the company of those rare and fine books, and their zealous guardian. It gave me a taste for antiquarian books, and initiated me into the rare book world. And while R may not have been the model exemplary bookseller, no one can say he wasn’t a first-class collector.

Users Today : 0

Users Today : 0

Leave a Reply