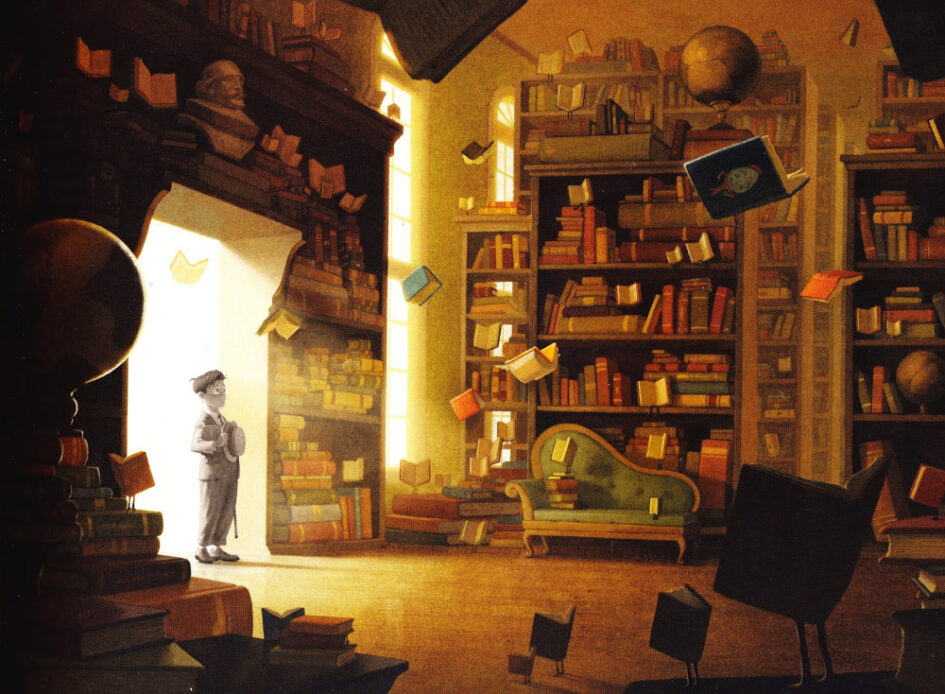

One favourite ritual of some book lovers is taking books off the shelves to re-arrange them. Mainly, you look forward to putting them back — “you remove them in haste but you labour over the rearrangement.” That familiar moment Walter Benjamin speaks of in Unpacking my Library when “the books are not yet on the shelves, not yet touched by the mild boredom of order.”

It gives me a chance every few months to physically handle all the books, stop to look closely at the book dust jacket or reread a passage that I remember. And then there is the anticipation of the new arrangement: how will I shelf them this time? As I begin reshelving my books, I realise with a little amusement that there actually is a fine, ongoing and peculiar tradition of other bibliophile-writers recording this activity.

The most quoted is Benjamin’s essay, but others, like Geoff Dyer, have picked up on this so tunefully that when speaking of unpacking his books, he’s referencing Benjamin’s essay without attribution.

The title of Dyer’s essay itself is a quote: Unpacking My Library. The undoubtedly fascinating author of Out of Sheer Rage states his bibliophilic ambition right at the start: to assemble all his books in one room. He’s wanted to do this his whole life. He has been relentlessly rearranging, staying up till three in the morning.

“Nothing highlights the fascination of unpacking more clearly than the difficulty of stopping this activity.” (That’s the German idealist-Jewish mystic he’s quoting). And this is true: lifting and carting books all day is one of the few labour-intensive activities that you don’t want to see come to a halt. Because, once the books are where they should be (“coldly ranged on the shelves” as Aziz once blurted to Fielding in A Passage to India), there is that mild twinge of disappointment that Benjamin observed.

Trying to shelve authors he likes together, Dyer finds there are too many “rogue volumes” — books of varying sizes — that spoil the arrangement. But these, and other shelving intricacies, are for this bibliomane (books are the only things he has cared to own) “a source of unresolvable pleasure.” He looks inside the flyleaf of one book and sees he has noted where he bought it: Algiers. Then he confesses it was actually from Foyles on Charing Cross Road. It was more glamorous to put down where he had read it than where he had bought it. The books are now finally in one room. A life’s ambition is near completion, and he’s content to just sit beside these books and purr. He has no desire to read the books, only touch them, perhaps smell them, because books are meant “to be arranged and classified, shuffled around.”

He feels bad, all of a sudden, for the people out there, just outside his window, who are not here in “this lovely lamp-lit solitude, surrounded by books.” Dyer also discovers how difficult it is to decide what books to keep and what books to chuck out. The very books he put away in a box to be sold are back on his shelf now. Part of the pleasure of shuffling books around is the illusion that you can let many of your books go — either to make more room or from an old impulse that you can do without many of these books.

Once, in a fit to streamline my book-cluttered apartment, I decided to cut down my library to what I hoped would be an essential collection: the kind I had when I was a student and had just begun to collect the works of writers I admired. A deeply personal collection that identified me not as a book lover, but simply as a being that belonged to those pre-collector times. Then, there were only a handful of books, but I knew every one of them intimately — I had read and reread them all.

I couldn’t bear the idea of unread books on a shelf. Books, I realised, can clutter your bookshelf. I wanted to simplify, resist complication, and did not want to be encumbered by obsession. So I began the trimming process with books and writers that I once felt a deep connection to, but who now seemed to fall away when I revisited them. It isn’t the book but me that had changed — I was not the same reader I once was.

Not surprisingly, I didn’t find it easy to let go of them. Ah, the joys and snares of reading — who can predict them? Now I feel the need to have books that I am yet to read, yet to open. Like friends I can call on unexpectedly. I don’t like the idea of an essential collection anymore. It seems to define me too much; as if I couldn’t conceive of other friendships, enter other worlds. Luckily, we don’t outgrow all the authors of our youth; some just get better.

This pleasurable, absorbing ritual of rearranging books now seems to me really about getting to know your books all over again. To pick one from the shelf, to remember where and when it was bought, and to recall the pleasure finding the book has given you — this is why a bibliophile gets all her books off and on the shelves every year.

Users Today : 0

Users Today : 0

Leave a Reply