It makes you wonder, doesn’t it, why we collect at all? Not just books — why do we collect anything? The theorist Jean Baudrillard undertook to answer this in several essays. His conclusions are not the cheeriest. The impulse to collect, he declared grandly, is regressive, the passion, escapist and the gratification, illusory!

The objects we collect, he pointed out, mirror us: “Here lies the whole miracle of collecting. For it is invariably oneself that one collects.” And so it would seem the goal — at least one of them — in collecting is to never complete a collection. Because to complete a collection is a kind of death.

The elusive object is what a collector is after. To find everything one is looking for takes away the pleasure of the pursuit; the chase, the hunt for the missing object is what drives a collector. (Which is why the father of modern book collecting, ASW Rosenbach, once famously quipped: “Next to love, collecting is the greatest sport.”)

Baudrillard points to one other crucial factor in the impulse to collect: That in an age of “faltering religious and ideological authorities,” objects “are by way of becoming the consolation of consolation, an everyday myth capable of absorbing all our anxieties about time and death.” At the heart of collecting is also a need to find order. Even to find oneself. It requires desire, knowledge, curiosity, pursuit and observation. Any modern person can tell you how hard it is to invest in human relationships, but to invest in things is easier. You can depend on things, trust them. Control them. The object is the perfect pet! And I suppose it isn’t far fetched to think of the things we collect as toys for adults to play with.

Bold and bizarre

Invariably, in talking about collecting, the bizarre crops up: People who collect strange things. Not just high art but kitsch, too. And tales of extreme forms of collecting, and deadly obsessions. Paul Theroux once profiled an Anthony Burgess collector (probably fictional but no less interesting for it) in the New Yorker, who, in addition to owning everything Burgess had ever written, also possessed two old passports of Burgess, some concert tickets he had once used and an umbrella he had left behind at a bookshop.

Bibliomania, Flaubert’s first published story (he was 15) perfectly illustrates how it can all go very wrong. The story is about a Spanish monk who was ‘literally willing to kill to possess a book he wanted for his collection.’

Flaubert actually based it on a true case of bibliomania. In 1830, a Spanish monk named Don Vincente looted his own monastery’s library of rare books, left the order and a few months later surfaced as an antiquarian bookseller in Barcelona! People grew suspicious, but those were the early days of bibliomania and few knew how exactly the mania manifested. Soon, the former monk turned book dealer was showing more interest in buying books than selling them. ‘For own use only’, he would say when someone asked to buy a book from his bookshop. In 1836, a rival bookseller won the bid at a book auction for a coveted rare volume, the only surviving copy of Edicts for Valencia, printed in 1482 by Spain’s first printer, Lamberto Palmart.

Don Vincente bid everything he owned for the book in the auction but was outbid by a syndicate of rival booksellers led by Augustino Paxtot. Three days later Paxtot was found dead in his bookshop. The clues pointed to Don Vincente, and the authorities found all the books that had gone missing or had been stolen in Barcelona.

The former monk had not sold a single item, although he could have become rich by putting them on the market. ‘I am not a thief,’ he declared at his trial. And added that sooner or later people had to die, but books needed to be preserved, looked after. But the true nature of Don Vincente’s bibliomania would only surface at the end of the trial.

Trying to establish his innocence, his lawyer unearthed another existing copy of the Edicts in Paris and used it as evidence to show that Vincente’s book was not necessarily Paxtot’s. The monk went into shock. From that day until the day of his death, he was heard to mumble constantly, ‘My copy is not unique, my copy is not unique, my copy is not unique.’ A year later, word of this monk’s deeds reached the ears of young Gustave.

Flaubert shaped this into a twisty little tale about a bookseller’s homicidal quest to own the only known copy of a book to exist in the world.

Smart investment

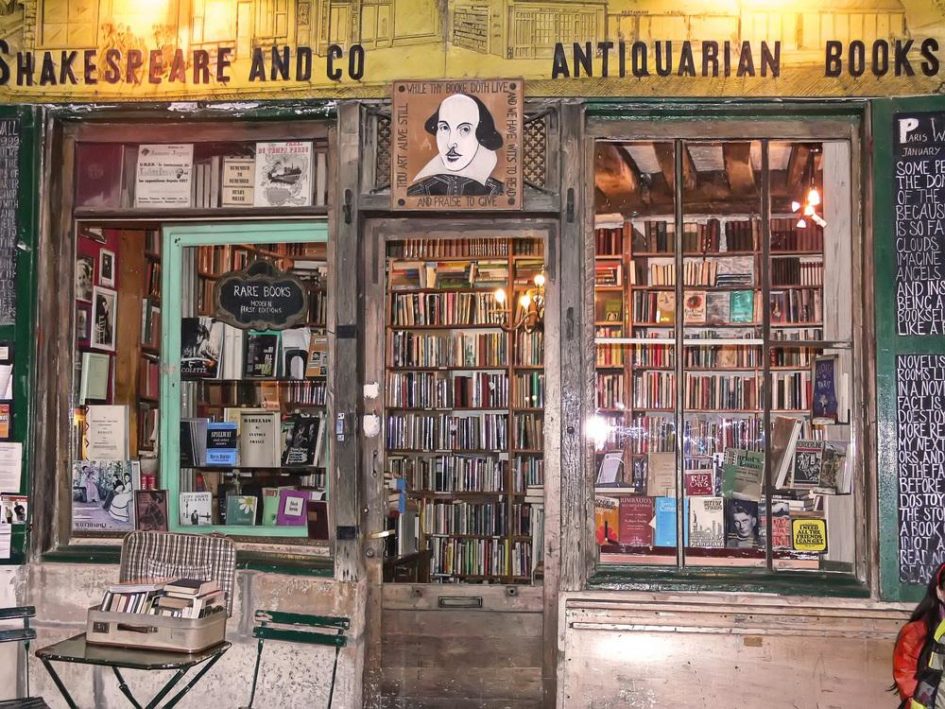

Like I said: We can’t resist demonising collecting. However, closer to the real picture, and what is more commonplace in the world of collecting, is that if done knowledgeably and tastefully, collecting is a smart, shrewd investment. As a serious book collector what I often mourn is the lack of a book collecting tradition in India, and the absence of a vibrant antiquarian book market here. The only form of collecting that has an established market place here, and which is taken seriously, is acquiring, buying and selling art.

Paintings mainly, and sculpture.

There are serious players here: Art collectors and auction houses with plump lavish catalogues. We’ve managed to evaluate our paintings and arrived at a price for them; more significantly we have learnt to value them, take care of them, restore them — in a way that we’ve never done with our books.

The Osians Auction House in Mumbai and Delhi has their ABC auction series (Art, Book, Cinema) for many years now. Vintage Hindi movie posters are up for auction along with books and monographs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The condition as noted in the ABC catalogues for some of these books are fair to middling. Often rebound. In our secondhand bookshops which sometimes double as (laughably poor) antiquarian stores you’ll be lucky to find anything truly rare or valuable — and if you do, I can bet that it’s condition will be poor. In tatters, and falling apart. Entirely diminishing its value, and its original, unrestored beauty.

Over the years I’ve looked futilely in our bookstores for modern first editions of famous Indian English novels. Something such as, say, a first edition of Narayan’s The Guide or Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines or Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English, August.

If I did find one or two copies, they were missing the dust jacket or the dj was torn, or the binding was loose, or the book itself was so soiled, it was uncollectible. So, guess where I eventually found fine editions of these books and in pristine condition? In bookstores abroad! The care and value we should have bestowed on our books, these foreign booksellers had lavished on them instead. The dust jackets were intact and protected in archival quality Mylar jacket sleeves.

It is high time that we begin paying attention to and caring for our rare antiquarian and modern books, monographs, pamphlets, broadsides and other paper ephemera in the way we have always cared for our art — as our heritage, as something beautiful to touch and behold. And perhaps most importantly: As venerated objects of our culture.

Users Today : 0

Users Today : 0

Leave a Reply